BBC News

Family bulletin

Family bulletinIn January, Lina went to the police.

Her former partner was threatening her at her home in the Spanish coastal town of benalmádena. On that day, he claimed that he raised his hand as if he was hitting it.

“There were violent rings – they were afraid.”

When she arrived at the police station, her case was interviewed and recorded in Viogén, a digital tool that evaluates the possibility that a woman will be attacked again by the man himself.

Vojin – a system based on algorithm – asks 35 questions about ill -treatment and its intensity, the attacker’s arrival to the weapons, his mental health and whether the woman has left, or thinks about leaving, the relationship.

Then its threat is recorded as “small”, “low”, “medium”, “high” or “extremist”.

The category is used to make decisions to allocate police resources to protect women.

Lina considered that she was in a “medium” risk.

She asked for a restriction in a sexual violence court specialized in Malaga, so that her former partner could not be in contact with her or sharing her living space. The request has been rejected.

Her cousin says: “Lina wanted to change the locks in her home, so that she could live in peace with her children.”

Three weeks later, she was dead. It was claimed that her partner used his key to enter her apartment and soon the house was burning.

While her children, mother, and former partner fled, Lina did not. Her 11 -year -old son was widely reported that he was telling the police that it was his father who killed his mother.

Lina’s body without life was recovered from the charred interior of her home. Her ex -partner, the father of her three young children, was arrested.

Now, her death raises questions about Fujin and her ability to maintain the safe women in Spain.

Viogén did not carefully predict the threat of Lina.

As a woman intended for a “medium” risk, the protocol is that she will be followed again by a candidate police officer within 30 days.

But Lina was dead before that. If the “high” risk, the police follow -up would have occurred within a week. Was this a difference in Lina?

The tools needed to assess the threat of domestic violence in North America and through Europe are used. In the UK, some DARA police forces use (home abuse risk assessment) – mainly a reference list. Dash (domestic treatment, chase, harassment and assessment of honor -based violence) may be employed by the police or others, such as social workers, to assess the risk of another attack.

But only in Spain is tightly woven algorithm in the police. Viogén has been developed by Spanish police and academics. It is used everywhere, regardless of the country of Basque and Akalonia (those areas have separate systems, although the country’s cooperation worldwide).

The head of the National Police Unit and the Women’s Unit in Malaga, ISS ISABEL ESPEJO, describes Viogén as “very important.”

“It helps us to follow the issue of every victim very precisely,” she says.

Its officers deals with 10 reports on sexual violence per day. Each month, Viogén is classified as nine or 10 women as being at risk of repetition.

The effects of resources in these cases are huge: the 24 -hour police protection for women until conditions change and the risks decrease. A woman who has been evaluated as a “high” risk may also get an officer.

A study conducted in 2014 found that the officers accepted the Fujin evaluation of the probability of abuse of repetition by 95 % of the time. Critics suggest that the police give up decision -making regarding women’s safety to a algorithm.

Cho Inspes Espejo says that algorithm calculation of risk is usually sufficient. But she realizes – although Lina’s case was not under her leadership – that there is something wrong with Lina’s evaluation.

“I will not say that Vogin does not fail – but this was not the trigger that killed this woman. The only guilty party is the person who killed Lina. Total security does not exist only,” she says.

But at a “medium” danger, Lina was never a priority for the police. Was Lina Vojin evaluation an impact on the court’s decision to deny it a restriction against its former partner?

The court authorities did not give us permission to meet the judge who deprived Lina of a judicial order against her former partner – a woman attacked on social media after Lina’s death.

Instead, Maria Del Carmen Guterres, with the last gender violence judges in Malaga, tells us that such something needs two things: evidence of the existence of a crime and the threat of the serious danger to the victim.

“Viogén is one of the elements that I use to assess this danger, but it is far from the only element,” she says.

The judge sometimes says, she issues restrictions in cases where Viogén evaluated a woman as in a “little” or “low” danger. On other occasions, you may conclude that there is no danger to a woman considered “medium” or “high” because of the risk of repetition of abuse.

Dr. Juan Jose Midina, a crime scientist at Seville University, says Spain has a “postal code lotion” for women who are applying for restrictions – some judicial states are more likely to give them more than others. But we do not systematically know how Viogén affects the courts, or the police, because studies have not been done.

He says: “How do police officers and other stakeholders use this tool, and how are their decisions to make? We have no good answers.”

The Ministry of Interior in Spain often allowed academics access to Viogén data. There was no independent scrutiny of the algorithm.

Jimma Galdon, founder of ECTAS – an organization that works on the social and moral influence of technology – says if you do not review these systems, you will not know if she is already delivering police protection to occasions women.

Examples of algorithm prejudice in other places well documented. In the United States, an analysis of 2016 of the Naksa tool was found that black defendants were more likely than their white peers who were incorrectly sentenced to being at risk of repeating the abuse. At the same time, the white defendants were more vulnerable than the black defendants who were misleading it as low risks.

In 2018, the Ministry of Interior in Spain did not provide a green light for the ECTAS proposal to conduct a secret internal review and supportive of the Pono. So instead, Gemma Galdon and her colleagues decided to unlike Viogén engineering and external audit.

They used interviews with home abuse survivors and information available to the public – including data from the elimination of women who were killed, such as Lina.

They found that between 2003 and 2021, 71 women were killed by their partners or former partners who previously reported the household abuse. That registered on the Viogén system was given risk levels of “minimal” or “medium”.

“What we would like to know is, were the errors that cannot be mitigated in any way? Or can we do something to improve how these systems are to set risks and protect these women better?” Jima Galdon asks.

Head of Sex Research in the Ministry of Interior in Spain, Juan Jose Lopez Osurio, refuses to investigate ECTAS: Not with Viogén data. “If you don’t have access to data, how can you explain it?” He says.

He is warning of external scrutiny, for fear that it may expose all to the safety of women whose cases are recorded and Fujin procedures.

“What we know is that as soon as a woman is reported to a man under police protection, the possibility of more violence is significantly reduced – we have no doubts about it,” says Lopez Osurio.

Fujin has evolved since it was presented in Spain. The questionnaire has been revised, and the “minimal” risk category will be canceled soon. Even critics agree that it makes sense to have a unified system that responds to sexual violence.

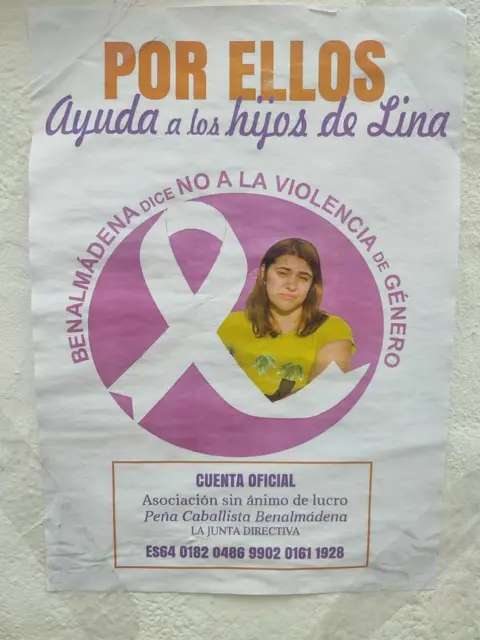

In Benalmádena, Lina’s house became a mausoleum.

She left the flowers, candles and pictures of the saints on the move. A small sticker stuck to the wall declared: Benmerna says not for sexual violence. Collection of community donations for children of Lina.

Her cousin, Daniel, says that everyone is still reeling from the news of her death.

He says: “The family destroyed – especially Lina’s mother.”

“82 years old. I don’t think anything is sad that your daughter was killed by the aggressor in a way that could be avoided. Children are still shock – they will need a lot of psychological help.”

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/branded_news/fbc2/live/2b813f50-1b11-11f0-96f2-e507ceb83400.jpg

Source link